Life in France, I try to tell people, is not so different from life in the U.S. There’s the socialism, sure, and the baguettes, and the little streets with their little cars. There are the tram networks, and the (generally) punctual trains. But once you start going to school or going to work, once you slip into your daily routine, it’s easy to forget you’re halfway around the world.

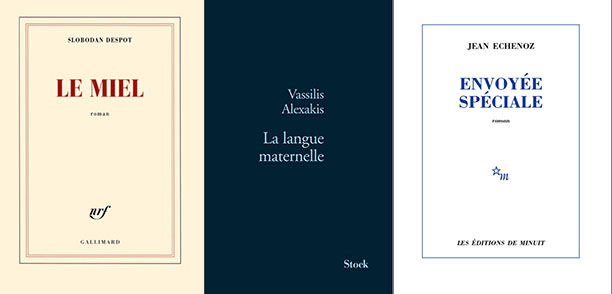

Until, that is, a cashier asks you to pay with coins, or you see one of those little cars trying to squeeze into an even littler parking spot. Or maybe the jolt comes when you walk into a bookstore and see a line of covers like this:

A bit different from the usual American fare, especially when you consider that the above titles come from reputable publishing houses. Esteemed ones, even. I suppose most French readers have been brought up to revere such covers, but for a foreigner like me, their starkness can inspire very different sentiments. In fact, if I didn’t know any better, I would think these books were self-published.[1]

So what’s the deal? Did the graphic design teams at Gallimard, Stock, and Éditions de Minuit suddenly go on vacation, or get the axe? Surely there’s no other reason to offer up shelf after shelf of such bland covers?

It would seem, in fact, that there is. Just as the French are often at their chic-est in all black, their best literature is dressed with simple elegance. Minimalist design, no bells and whistles, nothing to distract from the essence. Why add anything else, the thinking goes, when all the art you need is right there in the text?

This line of thought is precisely what has given us the covers you see above: the white[2] of Gallimard, the blue of Stock, and… the white of Éditions de Minuit. Stock is the elder statesman of the bunch, dating all the way back to 1708, while Gallimard’s Blanche (founded in 1911) seems to enjoy the most cachet, having become a veritable institution in the French publishing world.

Allowing a book to speak for itself in this way seems to me both bold and courageous. In the U.S., authors’ words are rarely granted such prominence.[3] Yet I can’t help but see the ‘pure cover’ as an imperfect model. There is no disputing the prestige that comes with inclusion in the Collection Blanche, but I have to wonder: how must it feel, as an author, to labor for years on your work, only to suddenly lose it amid a field of cloned covers?

What I see here is a kind of numbing homogeneity, a kind of creative stasis. There is something a little too easy about hiding behind a simple monochrome cover, book after book, year after year, decade after decade. And merely slapping an author’s picture on the cover does little to change the situation.

Not every French publisher is ‘guilty’ of producing plain covers, of course. The most notable example of the contrary is perhaps Hachette’s Livre de Poche (or ‘Pocket Book’).[4] Since its debut in 1953, the collection has given rise to more than twenty thousand books, each more colorful and vibrant than the next. Not all are the prettiest thing you’ll ever see (one of my non-favorites has to be this rendering of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein), but the Livre de Poche has had a massive and transformative impact on the French publishing industry. In 2013, the Paris Book Fair marked the collection’s 60th anniversary by showcasing more than a thousand of its covers from over the years.

I would like to see this phenomenon spread beyond mass-market books and into the realm of literary fiction. Both out of personal preference, and because all those ‘sober’ collections could use a little sprucing up. I recognize that they’re trying to offer high literature in its purest state. Fine. But at the same time, I can’t imagine a grand cru being sold with a bare label, and the same should go for books.

I was an English major in college, and I’ve been groomed to appreciate the classics. But I see no reason to present them as-is, without any visual hook. Far from detracting from the text, skillful graphic design can heighten the reading experience by getting our blood pumping the second we lay our eyes on the book. This allure, this seduction, is key to immersing yourself in a story, and shouldn’t be cast aside simply in the name of tradition.

More and more, I think publishers here are seeing that. It’s difficult to say for sure, given that analyzing cover trends often comes down to simply observing bookstore shelves, and clicking around online; but a transformation does seem to be taking place in France. One interesting example (taken somewhat arbitrarily) is Paulo Coelho’s international bestseller The Alchemist. One may note a considerable evolution between the following French covers, one from 1994 (published by Anne Carrière), and the other from 2012, in honor of the book’s 25th anniversary (published by Flammarion):

In terms of avant-garde graphic design, Flammarion’s psychedelic cover even bests the American anniversary edition (from HarperCollins):

Such experimental graphic design certainly isn’t for everyone, or every book. But you don’t need to be on the bleeding edge to have a strong visual impact. My favorite ‘pure cover’ collection is the Piccola Biblioteca, produced by Italian publisher Adelphi. The collection is nearing seven hundred titles, yet the covers never go stale. Simple changes in color and typography, as well as occasional graphic variations, ensure that each book remains unique:

Or better yet, we may take the example of Fabio Volo’s È tutta vita (Mondadori), a current bestseller:

Who could resist cracking the cover open and taking a peek inside? Aesthetically simple, yet attractive and intriguing, this design offers the perfect example of how to pay homage to an author’s creation while also selling it, in the most noble sense of the word. And isn’t that the ultimate goal, after all? To get books into readers’ hands?

I have done my best so far to steer clear of e-books, the rise of the smartphone, etc. But we are living in a technological and fast-paced world, where readers — even dedicated ones — are increasingly submerged by distractions and bombarded by stimuli. And in such tumultuous times, it would seem to me that bookmakers — the esteemed ones above all — have a duty to help them see through the fog.

———————————————————————————————————————————

For further reading, I recommend this informative article from Slate.fr (in French), similar in content, though with a slightly different approach (and conclusion).

———————————————————————————————————————————

———————————————————————————————————————————

Written by Christopher Bradley

[1] Which is by no means intended as a slight to self-publishers. I’m one myself, and am very familiar with the graphic design struggle; I’ve wanted many times to simply throw some text on the front and call it good.

[2] Well, cream, really, but it’s called the white (la Blanche).

[3] At least not in this way, and usually not in the realm of literary fiction. Our mega-bestsellers and celebrity writers tend to be confined to genre- and popular fiction.

[4] Hachette also happens to be the parent organization of Stock, mentioned above.